Revisiting Wright’s Vision of a ‘New Freedom’ for American Living in an Age of Global Pandemic

By Brian R. Hannan

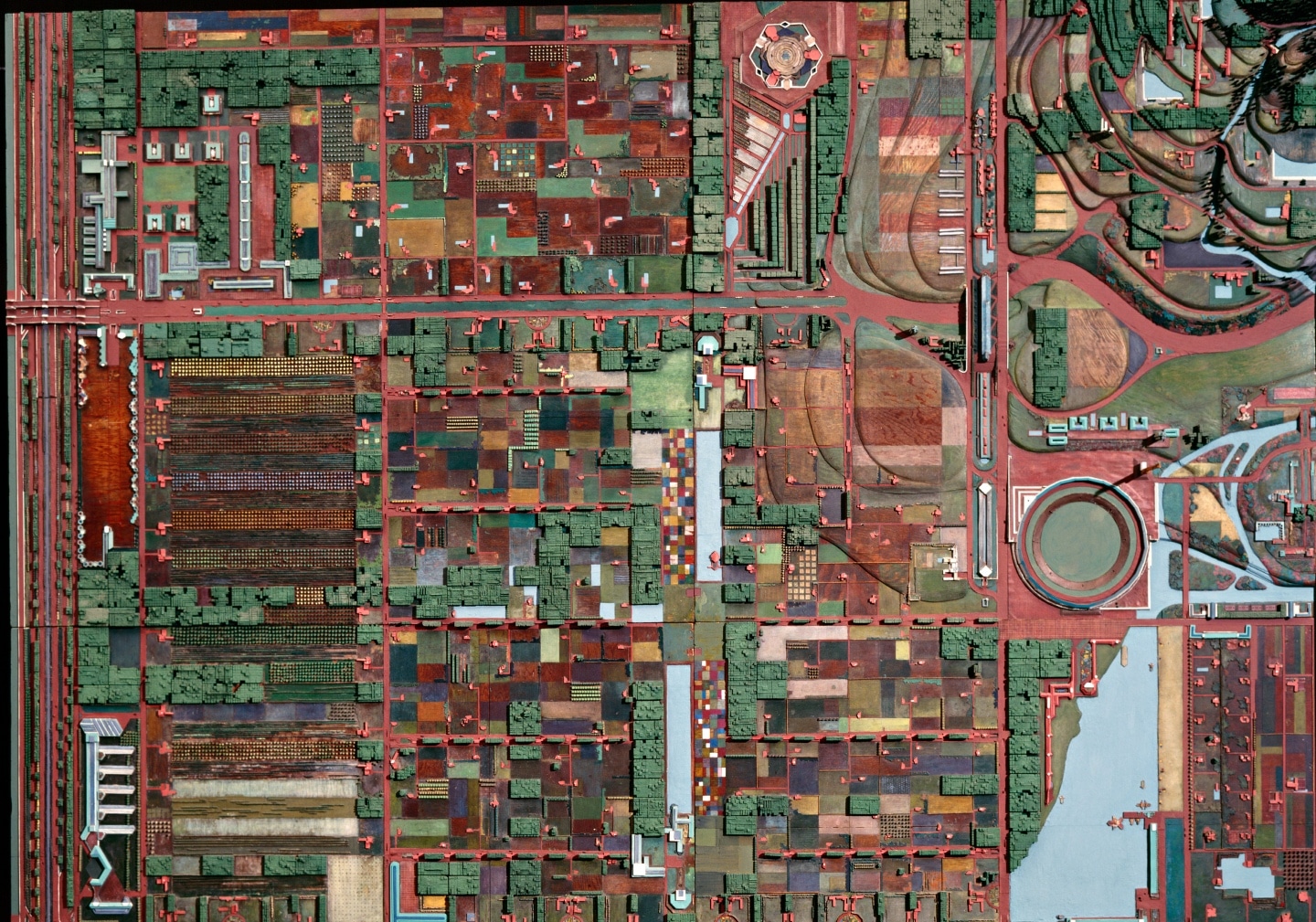

When Frank Lloyd Wright introduced Broadacre City to readers of “The New York Times Magazine” in March 1932, the United States was in the grips of the Great Depression and on the cusp of the Dust Bowl. As the concept evolved and the apprentices built a promotional model, he promised it would bring a “new freedom for living in America.”

“The Broadacre City is not merely the only democratic city,” Wright wrote. “It is the only possible city, looking toward the future.”

Nearly nine decades later, Broadacre City remains both a curiosity in the architect’s portfolio and a challenge. As we work to stop the spread of COVID-19 and shore up the economy, was Wright right? Could his utopian vision help to advance our own search for national and personal renewal in the postmodern era?

“It’s almost uncanny how perfect it would be in the current moment,” said Jennifer Gray, curator of drawings and archives at Columbia University’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library. “The pandemic has given people a chance to re-evaluate” how, even in the best of times, they’re forced to juggle competing professional obligations and personal commitments.

“People are waking up to that, and they realize they want to reset the balance.”

For Wright, Gray said, Broadacre City emerged as his response to overlapping concerns about the machine, densely populated cities — which he described as a “fibrous tumor” — and rising economic, political and social inequalities. She contends he conceived Broadacre City as a thought experiment rather than as a literal blueprint: How can the United States ease the urban-rural divide, reconnect citizens with nature and foster a renewed sense of autonomy and self-reliance?

In other words, “more agency,” Gray said. “They’re not dependent on the government or their boss or whatever else. I think that’s the whole idea.”

Home and land ownership emerged as the common denominator for Wright, who would assign each “Usonia” household a thoughtfully designed house atop a minimum of one acre — more for farms or families with children. Removing the distinction between landlords and tenants, while providing people with the means of growing their own food and selling the excess for profit, would eliminate much of the inequality he saw and bolster democracy.

Humane use of the machine would ensure societal needs were met while reducing the hours people worked. With more time, they could enjoy leisure, exercise, the arts and community and social activities. At four square miles, each self-contained-and-interconnected Broadacre City minimized commutes, reducing stress and congestion. Many workers could use the telephone to perform their duties at home, and radio would keep citizens informed.

“All common interests take place in a simple coordination wherein all are employed: little farms, little homes for industry, little factories, little schools, a little university…, little laboratories…,” Wright wrote. “Economic independence would be near, a subsistence certain; life varied and interesting.”

In the context of the COVID-19 outbreak, quarantining in place would be easier, and people need not fear eviction. Less density, when paired with social distancing, could translate into lower spread.

The downside? “You wouldn’t actually be able to do it,” Gray said, citing massive redistribution of wealth, prohibitive cost and wholesale restructuring. “It’s more about thinking through different ways of living and different ways of being in a community.

“So even if the solution is not Broadacre City, we can at least make improvements on things like education, local government, environmental sustainability, class disparity and gender and racial inequality,” she added. “I think it’s a way to think through these problems, and maybe we arrive at solutions that are more practical.”

The changes Wright envisioned with Broadacre City, occasionally reflecting his inclinations and idiosyncrasies — a car in every carport and not a power line in sight — were sweeping. Even he conceded in a 1935 article for “Architectural Record” that “(t)here are too many details involved in the model of Broadacres to permit complete explanation. Study of the model is necessary study.”

Indeed, Wright would spend the rest of his life tinkering with Broadacre City and tweaking its central concepts. He filled three books and several articles with his musings and continually wove new architectural projects into the plywood tapestry: Beth Sholom Synagogue, The Illinois, the Marin County Civic Center, Price Tower and various Usonian homes, among others.

The Broadacre City model last visited the Badger State in 2011 as part of an exhibit at the Milwaukee Art Museum: “Frank Lloyd Wright: Organic Architecture for the 21st Century.” At the time, the late Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, then archives director at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, told a reporter: “It seems like a good time to remind people that there was a good way in which architecture helped people live better and live in harmony not only with themselves but the planet they are living on.”

Gray agrees, phrasing in the present tense the renewed optimism she sees amid architects and the progress they can facilitate through coordinated, grassroots action — if not the top-down mandate of a Broadacre City. “We can change the society we live in,” she said. “We don’t have to take the status quo.”

For Further Reading

• “Broadacre City: An Architect’s Vision,” “The New York Times Sunday Magazine,” March 20, 1932

• “The Disappearing City,” Frank Lloyd Wright, William Farquhar Payson, 1935

• “Broadacre City: A New Community Plan,” “Architectural Record,” 1935

• “When Democracy Builds,” Frank Lloyd Wright, University of Chicago Press, 1945

• “The Living City,” Frank Lloyd Wright, Horizon Press, 1958