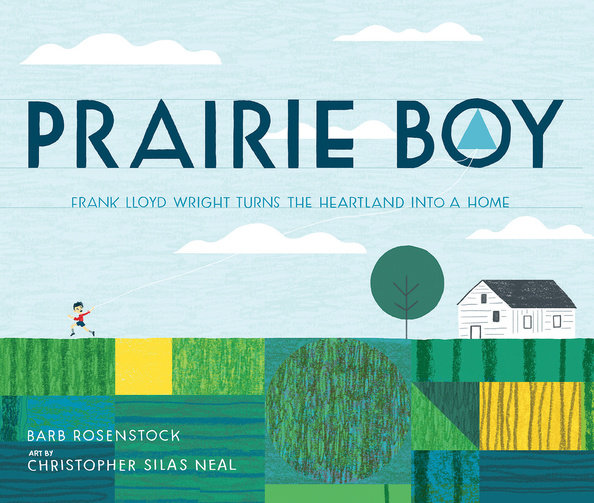

New Biography Explores Wright’s Childhood Interests, Adult Achievements

By Brian R. Hannan

Long before he put pencil to paper and penned a new chapter in the story of American architecture, Barb Rosenstock reminds us, Frank Lloyd Wright was a boy. A “prairie boy,” that is, who fell in love with shapes.

“Frank Lloyd Wright took his first breath on the Wisconsin prairie,” she writes. “He crawled in the paths of brush-footed butterflies and toddled through waves of tall grass … growing into the kind of boy who wondered … what makes the prairie feel like home?”

Helping to shape those musings, we learn in “Prairie Boy: Frank Lloyd Wright Turns the Heartland into a Home,” (Calkins Creek) is his mother, Anna. She gives him his first set of Froebel gifts – with a cube, a cylinder, a set of dowel rods, a sphere and three lengths of string – and sets him on an artistic path.

As Wright’s interest grows: “More blocks from Mother. Rectangles. Triangles. Half-moons” Rosenstock writes. “Frank set these new shapes on paper grids, studied sample pictures of pinwheels, crosses and stars. He shifted one shape to the next, turning piece by piece, his mind like a kaleidoscope.”

Years pass, Wright’s desire to be an architect deepening as he grows into an adult. Taking his first job as a draftsman in Chicago, Wright soon joins the well-known architecture firm Adler & Sullivan before opening his own shop.

“He sketched long, rectangular houses that snuggled into the flat plans,” Rosenstock writes. “He colored them in reds, browns and golds.”

In writing about Wright, Rosenstock said she hopes to encourage children to find and pursue their passion in life – not to copy someone else. It’s a theme she’s explored in the biographies for children she’s written about children who grew into well-known grownups: founding father Ben Franklin, photographer Dorothea Lange and painter Vincent van Gogh, among others.

“I stick really close to the child this person started as, and the actions of that child – and the interest of that child,” Rosenstock said. “The book is not set up as ‘be just like Frank.’ It is more set up like ‘your interests as a child have meaning, and they’re important.’ Wonderful things can come out of following what your brain and your hands tell you you’re interested in.”

“Prairie Boy” published in September 2019 – just weeks before a darker, adult examination of Wright’s life arrived in bookstores. In “Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright,” (Alfred A. Knopf) author Paul Hendrickson chronicles the conflagrations that defined Wright’s career and personal life. He explores the self-invention and reinvention Wright must have hoped would douse them.

By coincidence, both Rosenstock and Hendrickson trace their interest in Wright to childhood memories of the home he designed in Kankakee, Ill., for B. Harley Bradley. Rosenstock fondly recalls her father – a builder – taking her to see the Prairie School house.

Where the two books diverge, of course, is the level of detail they reveal about Wright’s personal life. Where Hendrickson’s Wright is fully realized, Rosenstock’s Wright is age-appropriate for the 7-to-10-year-old audience she has in mind.

Indeed, the Wright readers meet in “Prairie Boy” is a curious and precocious child. From the Wisconsin heartland he called home, he “built big dreams” and “turned architecture inside out.”

“Like magic, he shook dozens of shapes from his shirtsleeves – ovals, hexagons, triangles, cubes, spheres and cylinders,” Rosenstock writes in the book’s final pages. “Frank’s buildings grew like children, like grasses, like the earth itself.”

Editor’s Note: Visit barbrosenstock.com to learn more about the author and to download educational resources for “Prairie Boy.”